On the simple life

-- From The New Yorker's really smart profile of Don Culcord, the druggist who owns the only pharmacy in very rural Nucla, Colorado. Ken Jenks, quoted above, is a physician's assistant and the region's main medical expert.

Jenks grew up in Salt Lake City, but he has spent most of his working life in small towns. “Maybe I can describe it this way,” he says. “I like to play chess. I moved to a small town, and nobody played chess there, but one guy challenged me to checkers. I always thought it was kind of a simple game, but I accepted. And he beat me nine or ten games in a row. That’s sort of like living in a small town. It’s a simpler game, but it’s played to a higher level.”

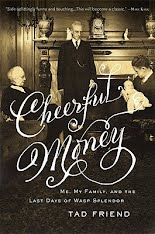

On WASPiness

Another great find from this week's NYTimes Book Review is New Yorker writer Tad Friend's memoir, "Cheerful Money: Me, My Family, and the Last Days of Wasp Splendor.

The Times pithily describes Friend's book as recounting "with amiable nostalgia, the foibles and predilections of a declining caste." Although I'm not exactly from the Nantucket-summer-home set, I can certainly relate in a general way to some of the idiosyncrasies he describes.

A couple good excerpts:

“If Catholic guilt is ‘I’ve been bad’ and Jewish guilt is ‘You’ve been bad,’ then WASP guilt is ‘You probably think I’ve been bad.’ ”

“Visible striving or seriousness of purpose is unWASP because it suggests that you aren't yet at-- haven't always been at-- the top."

Amerika!

The great thing about the New Yorker recently is that no matter what the subject-- whether it's a breezy shopping article by Patricia Marx or a multi-part essay about Ian Frazier's travels in Siberia-- it's really fun to read. Even when a story is hugely informative, reading it rarely feels like I'm eating my vegetables.

And that wasn't a hypothetical thing, the long Siberia travel essay. I actually read Part I last week. I especially liked Frazier's antecdote about how Siberia and America are similar in that they "both exist as constructs, expressions of the mind" to each other. You know how someone might say he parked "out in Siberia" if the only spot he could find was, say, four blocks from his apartment? It turns out being "in America" has a very definite connotation in Siberia, as well:

"The time was late evening; darkness had fallen. [An acquaintance and native of Siberia] led us from room to room, throwing on all the lights and pointing out the amenities. When we got to the kitchen, he flipped the switch but the light did not go on. This seemed to upset him. He fooled with the switch, then hurried off and came back with a stepladder. Mounting it, he removed the glass globe from the overhead light and unscrewed the bulb. He climbed down, put globe and bulb on the counter, took a fresh bulb, and ascended again. He reached up and screwed the new bulb into the socket. After a few twists, the light came on.

He turned to us and spread his arms wide, indicating the beams brightly filling the room. 'Ahhh,' he said, triumphantly. 'Amerika!'"

'We didn't sit around looking at screens.'

Have you read Ariel Levy's stuff in the New Yorker lately? I can't really offer a better critique of her work than Emily Gould's assessment earlier this year: "Ariel Levy is completely taking the New Yorker to school and using it

to clean the blackboard and then writing some new stuff on the

blackboard which is awesome."

Levy's article this week is centered largely around her interview with Lamar Van Dyke, a truly free-living Vietnam War era radical feminist lesbian who is now a grandmother in her 60's (but still really bad ass.) Although you really should just pick up the March 2nd issue and read the article-- you can't find it online-- I thought the last couple of paragraphs were especially worth sharing.

Regardless of the different people of different genders she has chosen over the years as her comrades, Van Dyke's primary loyalty has always been to her own adventure. A woman in her sixties who has been resolutely doing as she pleases for as long as she can remember is not easy to come by, in movies or in books, or in life.

"Your generation wants to fit in," she told me, for the second time. "Gays in the military and gay marriage? This is what you guys have come up with?" There was no contempt in her voice; it was something else-- an almost incredulous maternal disappointment. "We didn't sit around looking at our phone or looking at our computer or looking at the television-- we didn't sit around looking at screens," she said. "We didn't wait for a screen to give us a signal to do something. We were off doing whatever we wanted."

And, I know this is my second "Remind me why we are on the Internet, anyway?" post in as many days. I'm not sure what that says.

Levy's article this week is centered largely around her interview with Lamar Van Dyke, a truly free-living Vietnam War era radical feminist lesbian who is now a grandmother in her 60's (but still really bad ass.) Although you really should just pick up the March 2nd issue and read the article-- you can't find it online-- I thought the last couple of paragraphs were especially worth sharing.

Regardless of the different people of different genders she has chosen over the years as her comrades, Van Dyke's primary loyalty has always been to her own adventure. A woman in her sixties who has been resolutely doing as she pleases for as long as she can remember is not easy to come by, in movies or in books, or in life.

"Your generation wants to fit in," she told me, for the second time. "Gays in the military and gay marriage? This is what you guys have come up with?" There was no contempt in her voice; it was something else-- an almost incredulous maternal disappointment. "We didn't sit around looking at our phone or looking at our computer or looking at the television-- we didn't sit around looking at screens," she said. "We didn't wait for a screen to give us a signal to do something. We were off doing whatever we wanted."

And, I know this is my second "Remind me why we are on the Internet, anyway?" post in as many days. I'm not sure what that says.